|

Working

for a period of years on a daily newspaper is a great education,

especially in a place like Palermo, where at any moment you

might see someone you knew -a policeman, a journalist, a magistrate-

killed by an assassin. And so we told ourselves that we could

no longer go on being passive witnesses to these massacres:

we had in our hands a tool that could be used to inform people

and to combat the phenomenon by helping to forge a new awareness.

At that time, the word "mafia" could not be pronounced

in a public place. Everyone was terrorised. We began to organise

exhibitions of photographs to denounce the Mafia and expose

its true face. In a newspaper, this sort of thing remains

superficial, ephemeral, sporadic; while an exhibition of photographs,

displayed all together in a public place, immediately reveals

the gravity of the situation and the responsibilities that

lie behind it. I remember the first exhibition we put together:

it was shown in schools, in villages, in town squares. People

were afraid to come up and take a close look at the pictures...

I also worked with the foreign press, the Americans, the British,

the French, the Japanese... I was their correspondent in Sicily.

In 1985 Letizia Battaglia submitted her portfolio for the

Eugene Smith Prize, and won it - that was an important international

recognition, and it encouraged us to continue.

In 1988 I was enrolled by the Magnum Agency.

This was a tremendous experience, for I had to leave Sicily

and work as a photographer for major magazines, dealing with

problems that had never come my way before. But with Magnum

there were problems of comprehension, and I didn't want to

lose my passion for photography. So after three years, I left.

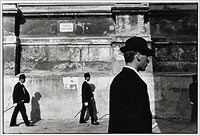

Working with Magnum gave me my first opportunity to travel

to the Eastern Bloc. This was before the Wall came down, and

it was still possible then to produce pictures in a neo-realistic

style, like the '50s in the West. And I was fascinated to

see that on the other side of Europe people lived a different

everyday reality, with different day-to-day problems. I began

to explore Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Romania, Czechoslovakia,

Bulgaria, Georgia... What mainly interested me in these countries

was their cultural, artistic, political and economic life.

In 1990 I spent four months working in Silesia (southwest

Poland), the most polluted region in Europe, on the effects

of pollution on health. I felt compelled to dig deeply into

all the associated social problems. This project also permitted

me to deliver the results of my investigation to the University

of Katowice in the form of an exhibition, which continues

to manage it to this day. This was accompanied by a written

report, which was approved by the University before the exhibition

was opened.

After the collapse of the communist regimes, the East became

a favourite playground for photo reporters. Events had left

me behind, and the newspapers and magazines were saturated

with facile and stereotyped pictures.

In 1991 I decided to go and live in Paris. My work denouncing

the Mafia was no longer as necessary as before: by this time

a collective awareness had developed and the subject was well

covered by the media. My life and work in Palermo was no longer

satisfying, and had become a pointless risk. I was a photographer

before I became the photographer of the Mafia, and this label

was hobbling my creative spirit. And so I abandoned a professionally

privileged position (for I had become internationally famous

for my work on the Mafia) to plunge into a marketplace that

was seriously affected by the economic crisis, and where I

had no certainty that I could make a place for myself.

|